Matthew Kilburn revisits Doctor Who and the Cybermen, the first Target novelisation written by Gerry Davis, and finds out what happens when the Second Doctor isn’t quite the Second Doctor, but owes something to the Third and Fourth, and leaves a legacy for the Twelfth. Originally presented as a talk at the first Target Book Club event at Bush Hall, London, on 16 July 2023.

Gerry Davis (1930-1991) was story editor of Doctor Who for just over a year. His first credit was on The Bell of Doom, the fourth episode of The Massacre of St Bartholomew’s Eve, on 26 February 1966; he bowed out with episode three of The Evil of the Daleks, on 3 June 1967. In that time, working with producer Innes Lloyd, he achieved the transformation of the series into a more resilient and more focused enterprise. The nature of the Doctor’s adventures was rethought with a greater emphasis on threat and horror, often centred on a single location which could be realised in a large set, the ‘base under siege’. New regular characters with definable backgrounds were introduced, with whom the audience could hopefully easily identify. After Lloyd apparently persuaded William Hartnell to leave, Davis led the successful reconception of the Doctor’s character so he could be played by Patrick Troughton. With Kit Pedler, Davis co-created a new regular adversary for the Doctor, the Cybermen; the evil represented hitherto by the Daleks was no longer so singular and could be shared with other representatives of antihumanity. It was as the creator of the Cybermen that Davis returned to Doctor Who in 1974 when he was commissioned to write for the expanding series of Target Doctor Who novelisations. He would write four books in the series, and cowrite another, over the space of eleven years.

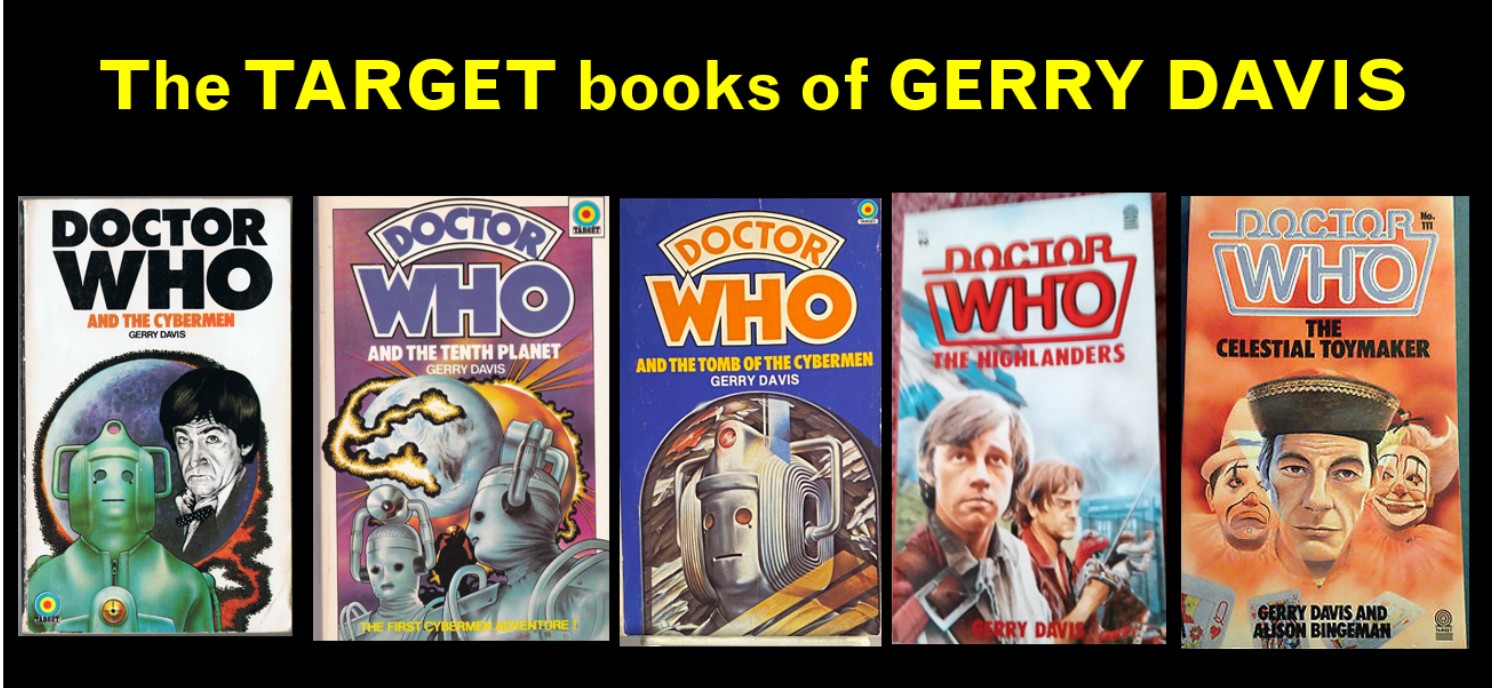

Davis’s contributions appear at different stages of the Target project. His first book’s cover uses the initial block letter logo, the next two the arch logo derived from Bernard Lodge’s 1973 diamond, and the final two have Sid Sutton’s 1980s neon logo. The first was published by Universal-Tandem at their Gloucester Road address in South Kensington, the second also from Gloucester Road but by Tandem Publishing after the former American owners, Universal Publishing and Distribution, had sold the company to the British Howard and Wyndham group. After the merger of Tandem with Howard and Wyndham’s other publishing interests, the last three books were published by the combined firm, W.H. Allen, from their upmarket premises at Hill Street in Mayfair. This article deals almost entirely with the first three of these books, and mainly with the first: Doctor Who and the Cybermen (1975), adapted from the 1967 story The Moonbase. The others were Doctor Who and the Tenth Planet (1976); Doctor Who and the Tomb of the Cybermen (1978). 1984’s Doctor Who – The Highlanders and 1986’s Doctor Who – The Celestial Toymaker, which was co-written with Alison Bingeman and added another author to a tale already disputed between many different hands.

Notoriously for some, the Cyberman on the original cover art of Doctor Who and the Cybermen is painted by Chris Achilleos from a photograph taken during location filming for The Invasion (1968), and not from The Moonbase. An Invasion Cyberman even made a return visit to Jeff Cummins’s cover for Doctor Who and the Tomb of the Cybermen, infuriating Cyber-design purists. Bill Donohoe’s replacement cover for Doctor Who and the Cybermen, in 1981, was presumably more acceptable. BBC Books, of course, revived the Chris Achilleos cover.

What was going on? One answer, the prosaic one, was the absence of accurate reference material. More authentic Cybermen appear in Alan Willow’s interior illustrations, however. The other is perhaps more interesting, and makes the use of a ‘modern’ Invasion Cyberman (already over half the series’ lifetime away by 1975) more fitting. Gerry Davis came in at the end of the first wave of 1970s Target authors, but as story editor from 1966 to 1967 had a claim to have authored some of the fundamentals of Doctor Who. He had left less than a year before Terrance Dicks joined the series, someone who was probably always a successor from Davis’s point of view, working on something Davis had moved on from. Nevertheless, Dicks was the co-shaper of Doctor Who as it stood in the 1970s, an adventure series with a strong streak of reflection on environmental concerns, equality, and moral obligation to one’s fellows. It was also the willingness of Dicks to write new Doctor Who novelisations and find other people to help which enabled the Target range to progress beyond its initial exhumation of three mid-1960s titles. Davis was the first of the authors commissioned by Target not to have worked with Terrance Dicks on the Jon Pertwee era, and was as such an outlier. I’d argue that what we see in Doctor Who and the Cybermen particularly is a clash between the conventions which had already been established in the Target Doctor Who series, largely by Terrance Dicks, and Gerry Davis’s vision of what Doctor Who was.

Doctor Who and the Cybermen doesn’t just have the wrong Cyberman on the cover, but Gerry Davis makes Ben and Polly come from the wrong decade. They relocate in time from the 1960s to the 1970s. For Davis, this was most true to the intentions behind the creation of Ben and Polly. They are introduced on television as aggressively, almost caricatured, contemporary types, in reaction to their less rooted predecessors Steven and Dodo. In the book, Davis could have presented Ben and Polly as period characters, representatives of the Doctor’s visit to a recent past which was prehistoric to many of his young readers, but this wouldn’t have been true to the thinking behind their origins. Contemporary characters need to remain contemporary to their audience. So Ben and Polly had to be firmly associated with the present, so their home decade becomes the 1970s – and it remains so in Davis’s subsequent work.

In chapter seven of Doctor Who and the Tenth Planet, ‘Battle in the Projection Room’, Ben finds a James Bond film starring Roger Moore (probably The Man with the Golden Gun, from the mention of karate students) in the cinema at Snowcap base. He remarks that he had seen it a few weeks ago, before correcting himself, and remembering that he was in the year 2000, the book having relocated events from the television serial’s 1986. Ben practically invites Bond to join him in the book and take on the Cybermen, both a 1970s reference and a playful challenge to a cinematic blockbuster from a children’s novelisation. Later, in chapter ten, ‘Prepare to Blast Off’, Ben finds that he can’t break the lock on the cabin door. “They didn’t have locks like this in the 1970s,” he exclaims.

Even after Ben and Polly had gone, Davis was keen to emphasise that they were from what he presumed was the reader’s own decade. In Doctor Who and the Tomb of the Cybermen, when Victoria replaces her nineteenth-century outfit with “a simple dress that ended just above the knee,” Davis informed the reader that it had been left behind by Polly, “the girl from the 1970s.” This only changes in Doctor Who – The Highlanders, when Davis says Polly came from the 1960s. By 1984, Polly was firmly historical too, her original context too far removed from the readers for her to be passed off as a contemporary character. The books now also acknowledged an older or informed fan audience who required facts – or received wisdom – about regular television series characters to be respected rather than overwritten. Perhaps, too, Davis acknowledged Doctor Who’s institutional status, something arguably created by Terrance Dicks when he was script editor. Doctor Who asserted that it was not ephemera but something with a past, which was demonstrably evolving through different stages and which invited viewers and readers to take it seriously.

Returning to Doctor Who and the Cybermen, if Ben and Polly come from the present, what about their fellow-travellers? Davis isn’t particularly generous towards the past, which is always somewhere from which we’ve advanced. Nor is he kind towards Jamie McCrimmon, a character he created for The Highlanders at the end of 1966. He suggests that average eighteenth-century minds couldn’t adapt to travel in the TARDIS and that Jamie only manages it because he is “thick”. This attitude contrasts with the principles of Doctor Who established in an earlier Target book, the 1973 reissue of David Whitaker’s 1966 novel Doctor Who and the Crusaders, where the Christians and Muslims in conflict have every bit as much sophistication as people do in the reader’s own day. Instead, far more than on television, the audience is assumed to see Jamie as a ‘primitive’. I won’t go into Davis’s use of national or regional characteristics as a way of differentiating individual characters here; but in Doctor Who and the Tomb of the Cybermen, Davis treats Jamie as a more heroic figure, “strong Jamie” who pulled redcoats from their horses at Culloden, though he remains someone whose heroism is founded in brute force rather than intelligence.

What, though, of the Doctor? Gerry Davis’s Doctor is curiously, in his own way, a native of the past too. The crucial scene is carried over from the television version, with some changes. The Doctor owns up to a medical degree, and mentions “Edinburgh, 1870… Lister.” Joseph Lister was indeed professor of clinical surgery at the University of Edinburgh from 1869 to 1877. Davis corrects the suggestion in The Moonbase that the Doctor studied under Lister in Glasgow in 1888, a point when Lister was professor of surgery at King’s College, London. As in the television story, Polly has to urge the Doctor to think of discoveries Lister wouldn’t have known about, as if otherwise the Doctor would be treating twenty-first century patients with the knowledge of the nineteenth.

The TARDIS is described in language which seems slightly archaic as well. It doesn’t have a control room, but a cabin, fitted with padded bulkheads. It’s specifically compared to a seagoing vessel. Only the “hexagonal control desk” is recognisable. Davis’s books refer to clothes – including the dress Victoria apparently inherits from Polly – being stored in the TARDIS “equipment room.” Davis’s TARDIS has echoes of a vessel from a heroic age of scientific exploration, as if it belonged to a boys’ story’s retelling of the seagoing voyages of Shackleton or Scott; it’s a simpler and more confined vision of the ship than the limitless one Doctor Who’s audience would have derived from some of the other books.

Davis avoids initial physical descriptions of the regulars, except Polly, who (we are told) has long legs and a short skirt. The picture that Doctor Who and the Cybermen builds of the Doctor isn’t quite one of Patrick Troughton. When he sheds his space suit in the Gravitron room, he reveals “a too-long down-at-heels black frock coat that had seen much better days, baggy striped trousers and a large, very floppy red cravat.” The frock coat is right, but what of the rest? This is a slightly more flamboyant, theatrical outfit for the Doctor than the Second Doctor’s. This might be Gerry Davis, seven years away from his departure from the series, misremembering what Patrick Troughton wore in the role; or it might be deliberate distancing. Davis also has this Doctor striding down a corridor with long legs, Ben having to jog to keep up with him. This definitely isn’t the Second Doctor as already established in the books – the “small man in an ancient black coat and a pair of check trousers” with “a gentle, rather comical face and a shock of untidy black hair” introduced to readers by Terrance Dicks at the start of Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion.

Davis’s need for immediacy is responsible. I think he’s writing for an ideal Doctor, drawing not only on Troughton but on Jon Pertwee and probably also Tom Baker. I’m not sure he was fully on board with the idea that the series should acknowledge that there were multiple incarnations of the Doctor, and that this part of series lore could be part of the storytelling. In an early interview Davis seemed dismissive of attempts to give the transformation of William Hartnell into Patrick Troughton – which he wrote – a great mythological significance; it was just a device to get round the change of actors. Nevertheless, in his second Target book, Doctor Who and the Tenth Planet, mentions of “the old Doctor” prepare the reader for the stranger who introduces himself as “the new Doctor” at the end of the novel.

Davis must have written Doctor Who and the Cybermen within months of his return to writing Doctor Who for television. The commissions might even have overlapped. Gerry Davis was asked to contribute a Cybermen serial for Tom Baker’s first year, which became Revenge of the Cybermen, the initial storyline being commissioned on 9 May 1974.

Production documents show that Gerry Davis had seen “the first changeover episode” during July 1974. This was presumably part one of Robot, five months before transmission. The long-legged Doctor in Doctor Who and the Cybermen is physically closer to the actors the young mid-1970s reader-viewer recognised, while retaining Davis’s view of the Doctor’s character, which is more detached, ‘dreamy’ than either the third or fourth Doctors were on screen.

This is speculation rather than fact, but I wonder if Doctor Who and the Cybermen also reflects the disagreements between the Doctor Who production office and Davis. Davis called his story ‘Return of the Cybermen’. Script editor Robert Holmes insisted that it be titled Revenge of the Cybermen, which Davis disliked as it had been established in The Moonbase that Cybermen didn’t understand the concept of revenge. Davis uses Doctor Who and the Cybermen to reinforce this view. The reader learns in chapter one that “revenge was not a part of their mental makeup any more than the other emotions,” anticipating the later largely faithful adaptation in chapter eight of an exchange from episode three of The Moonbase. Cybermen are fortunate. They do not possess feelings.

Polly isn’t especially well-served by much of Doctor Who and the Cybermen, as she whimpers and wails and clings on to men. One of Robert Holmes’s notes to Gerry Davis on ‘Return’/Revenge of the Cybermen was the need to give her successor at five removes, Sarah Jane Smith, more prominence. Towards the end of the book, this works in Polly’s favour. It’s Polly and Jamie, rather than Ben and Jamie as on television, who take on the converted men and barricade them in the medical room. Later, Polly becomes joint witness with the Doctor of the expulsion of the Cybermen into space. It’s not enough for the otherworldly Doctor to be the reader’s eyes – Polly has to be there too. (Subsequently, Davis treats Victoria even more kindly: in Doctor Who and the Tomb of the Cybermen, her on-screen Mary Anningesque comparison of a Cybermat to a fossil is given a wider context, stating that she knew Michael Faraday and by implication other historical mid-nineteenth century scientific and intellectual figures.)

The oft-cited contradiction in the book is between the introductory first chapter, which states that the Cybermen originated on Telos, and the main body of the text, which follows The Moonbase in stating that some Cybermen left Mondas before it was destroyed. I wonder if the text we have is the result of a manuscript having to be submitted in the midst of redrafting, with Mondas and Telos in transit. The capitalization of the names in the text – MONDAS and TELOS – is odd and suggests they were capitalized to. make sure a typist got them right and this was carried forward into the book by Universal-Tandem’s relentless production process.

The opening passage from Doctor Who and the Cybermen, suitably amended, appeared in the three succeeding 1970s Doctor Who Cybermen books, including Terrance Dicks’s Doctor Who and the Revenge of the Cybermen, It evoked a lost civilization and the terrible choices it made.

‘Centuries ago by our Earth time, a race of men on the far-distant planet Telos sought immortality.’

The version in Doctor Who and the Tenth Planet suggests some Cybermen from Telos settled on Mondas, but Telos isn’t mentioned in the main text. Early fan writing was divided on the Mondas/ Telos issue. The distinction between Cybermen from Mondas and those from Telos is probably reflected in Peter Capaldi’s desire to encounter ‘Mondasian Cybermen’, which baffled fans who assumed Cybermen had always come from Mondas alone.

Towards the climax of Doctor Who and the Cybermen, the Doctor immerses himself in making calculations in his notebook as a kind of relaxation exercise. Peter Capaldi and/or Steven Moffat might have recalled this passage when working on the 2014 series of Doctor Who, when the Doctor developed a penchant for covering surfaces with equations. For Davis it’s an extension of the essential ‘dreamy’ state of the Doctor, often apparently disengaged from events. Davis’s Doctor has memory lapses and needs to check or write things down in his diary. There’s probably also some influence on another development in the Capaldi era. In The Woman Who Lived (2015) we discover that Me/Ashildr is reliant on shelves of diaries to accommodate a memory too long for her brain to support, rather like Davis’s Doctor.

Doctor Who and the Cybermen is a novelisation divided against itself, but those compartments, like the TARDIS bulkheads, are padded with thought and with concern for the integrity of past work and authorial vision. If Gerry Davis found, unlike Ben in Doctor Who and the Tenth Planet, that the projection room was under others’ command and full of unhelpful equipment, then he was going to do his best to show them how things could be done on his own terms, and then, like the professional he was, turning to work with others’ grain.